The following article is an excerpt of Bergfeld/ Bannys/ Bergfeld (2017): Resilient Family Business Systems. Achieving Longevity by Aligning Portfolio Strategies with Family Capabilities, to be presented at the Academy of Management Conference 2017, a leading international business research conference, at the Symposium on “Longevity and resilience at the interface of family, business and environment”.

The Great Wealth Transfer

During the next 30 years, over 40 trillion USD in assets will be transferred in the US alone – from the “baby boomer” generation to their children and grandchildren. The portfolios that constitute this “Great Wealth Transfer” include all sorts of financial assets, real estate, philanthropic engagements and operational companies. The receiving “Next Generation” of business families around the globe will be asked to steward these assets into the future. With the financial markets seeing extremely low interest rates for the foreseeable future, entrepreneurial action and operational companies will be a must-have in family portfolios that want to outperform exponential growth in numbers of family members over time.

However: Does the Next Generation truly have the capabilities needed to steward such entrepreneurial portfolios into the future? If portfolios are passed on to a receiving generation that might not have the capabilities to handle them, portfolio values and therefore family wealth are doomed to deteriorate. Often, business families forget to ask themselves this one essential question: Passing on is rather easy, but is the Next Generation really ready – from a truly objective point of view?

Some of the world’s leading business families have therefore started to proactively adapt and “clean up” portfolios and match them to the capabilities of the Next Generation. Such an approach can assist in smoothing the transfer as well as assuring the protection of the economic and social value in these portfolios. It also reduces the pressure and burden on the Next Generation and assures that inheriting portfolios becomes a platform for future prosperity and continued wealth creation, instead of life-sacrifice.

The present academic focus looks at the existence of certain family businesses or business portfolios, and dedicates attention to the positive and negative effects of the owning family, with all the known dynamics around the family, on the assets. Such analysis often starts with the family BUSINESS. However, there has been no bridging discussion yet between a family’s capabilities (with all the different building blocks of it) to own and control a portfolio, and a proactively designed “match” of the existing and future portfolio of entrepreneurial activities as a whole. Such an analysis has to start with the business FAMILY.

Family Capabilities Versus Family Portfolio

In short, the capabilities of one specific family might be ideal for a certain portfolio of entrepreneurial engagements, whilst the exact same portfolio might be doomed to fail for a different family with different capabilities. Hence, business families should be asset agnostic and capability conscious in order to structure their portfolios in such a way that wealth is preserved and grows, no matter through which asset type, in line with a potential change of a family’s capabilities from one generation to the next.

The conceptual model of “Family Capabilities versus Family Portfolio” consists of two building blocks: the “Capability Formula” and the identification of four possible “Portfolio Modules” that call for certain “Capability Levels”.

The concept of “Capabilities” amongst successors in family businesses has been analyzed for decades. The importance of knowledge and experience for and in succession processes has been well documented as well, and the importance that “owner-managers need to have capabilities, such as knowledge and skills, motivation and volition (willpower) and ‘affection’, when using their personal and institutional power” has been investigated too, although with a different focus. The importance of energy and resilience has been looked into intensively in recent years, especially in the entrepreneurship literature and the “bullet-proof” movement amongst young entrepreneurs.

The “Capability” term has been brought into a specific connection with a family business’ performance by numerous authors too. Herein, it is mentioned that the “Capacity to perform work […] is determined by level of complexity of mental processing”, where, “whether individuals actually apply their full potential capability is actually determined by their level of commitment, skills, and knowledge” (King, 2003, p. 175), and that it is essential to assess “… not only potential capability but also commitment to the business as well as skills and knowledge.” (ibid, p. 179).

King comes to the conclusion that: “If the future successor’s potential capability is not sufficient to handle the complexity of the business at the time the predecessor wants to retire, then an interim successor could be selected to manage and mentor the successor until he or she is ready. If that is not possible, then the business could be broken into smaller businesses or be sold. In the end, both the business and the family would be far better off, financially and emotionally, if the successor’s potential capability is in alignment with the complexity of the business” (ibid, p.181).

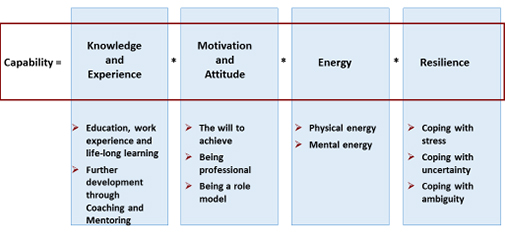

In combination of the above streams of literature, the “Capability Formula” for being a family business owner and/ or owner-operator reads as follows:

Four factors contribute to the “Capability Level” of an individual:

- Broad knowledge & experience, including well developed professional, personal and interpersonal skills;

- High motivation and a positive attitude, such as the will to achieve (Javidan, M. (2004), p. 240), perform and being a role model for others;

- A high level of physical and mental energy; and

- A high level of resilience, such as the ability to cope with stress, uncertainty and ambiguity – and also the complexity of mental processing to “reorient and restructure” (King, 2003, p. 175).

Managing complex portfolios in dynamic and highly competitive environments require a high level of capabilities of the Owners as well as the Executive Team. In the above description, it is important to note that in order to reach these high personal capability levels, all four factors have to be developed to a significant degree. This is indicated by the multiplicative nature of the individual factors. For example, low motivation or a negative attitude will result in an overall low level of capability of a family member of the Next Generation, even if the individual received the best education, is equipped with high levels of energy and has a strong resilience.

The Portfolio Perspective

The interwoven character of family and business development has been documented well since the beginning of the family business research field, e.g. in Kepner’s 1991 piece The Family and the Firm: A Coevolutionary Perspective. Nevertheless, it has not yet been argued sufficiently that the portfolio character and the capability levels of the outgoing as well as the incoming generations have to be aligned. Still, Next Generation may be pushed into leadership positions that are simply “too big” for their capability level, or do members of the Senior Generation try to achieve one more “big hit”, although their own personal capability (in particular the energy factor of the equation) is already decreasing significantly. Here, the well-researched “Impact of the Life Stage on [e.g.] Father-Son relationships in Family Companies” (Davis, J., Tagiuri, R. (1989) is neglected and not recognized.

As founders or successive generations begin to consider the end of their entrepreneurial career, the decision of sale versus continuity of the enterprise must be made. In the case of continuity, decisions must be made whether the next leader will be a member of the family versus a non-family member, or both. Before taking the decision if one or numerous member(s) of the Next Generation shall be assuming an active owner or owner-operator role from the Senior Generation, the available capability of these Next Generation family members has to be aligned with the actual and future “Capability Demand” of the portfolio. The capability demand of various assets in a portfolio can be determined by their current performance, their market environment, and the asset strategy being pursued.

- The current performance of the portfolio assets can oscillate between “very good” and “very bad”.

- The market environment can have the range between “very stable” and “being exposed to disruptions in the respective industry”.

- The pursued strategy can vary between “aggressive growth” and “stabilize the asset”.

The link between the family’s capability level and the various assets in a portfolio can therefore be built via four “zones” of a portfolio, shown below:

Portfolio zone 1 („Pleasant morning run “) is characterized by good to very good asset performance in stable market environments. This zone is an ideal “training ground” for members of the Next Generation with a low overall “Capability Factor” as a result of medium individual “Capability Factors”. This can, for example, be the case if Next Generation members are “just getting into understanding the business”.

Portfolio zone 2 (“Aspiring Professional”) is more challenging as a consequence of either a pursued aggressive growth strategy and/ or medium asset performance in a competitive market environment. Here, a medium overall “Capability Factor” is required as a result of high individual capability factors.

Portfolio zone 3 (“Marathon”) is very challenging because assets with low to very low performance have to be turned-around in very difficult market environments by stabilizing them or pursuing a moderate growth strategy at best. Only experienced leaders with high overall capability should be considered for these challenges.

Portfolio Zone 4 (“Iron Man”) is the most difficult one and should only be considered in exceptional cases. An aggressive growth strategy is pursued although the market environment is very difficult and the actual asset performance is low (or worse).

Combining the Family’s Capabilities and the Family’s Portfolio for a Swift Transfer

In a business family with multiple assets in a portfolio, a successful transfer of owner- or owner-operator-responsibilities from the Senior Generation to the Next Generation requires sufficient alignment between the capability demand of the portfolio as a whole, as a sum of the various assets in it, and the “Capability Supply” of the family, as a sum of the individual capabilities of the members of the Next Generation and the remaining capability level of the outgoing generation.

Ideally, the portfolio with its contextual factors, its business complexities and the foreseeable challenges is met by a Next Generation that has the appropriate capabilities, or the time to build these until “the time has come to lead”, in order to control a portfolio that calls for “Pleasant Morning Run”, “Aspiring Professionals”, “Marathon Man” or “Iron Man” owners.

Not all Next Generation owners need to be “Iron Men”, and maybe cannot be. And that’s totally OK, as long as the owning business family foresees the “mismatch” in cases of very complex and challenging portfolios, and either adapts the portfolio during the tenure of the Senior Generation, or builds a team and establishes other mechanisms that provide additional capabilities and support to the Next Generation leaders.

In addition to building adequate “support systems” and promote capabilities in the Next Generation (note: not all capabilities can be “nurtured”, some, such as motivation, are probably deeply rooted in upbringing, interests, circles of friends etc., and therefore almost impossible to “influence”), as additional support for swift succession processes, the Senior Generation can trigger three portfolio strategies:

- Proactively de-risking and simplifying the portfolio assists to hand over a stable and less challenging portfolio that needs less capabilities in the Next Generation. Also, it puts the Next Generation into a less burden-full situation when assuming the owner or owner-operator reigns. Here, a partial sell or strategic partnerships might apply.

- Assuring a well performing portfolio directed towards rather stable markets will assure that the reigns of owning or owning-operating can be handed over in rather calm waters, but a capability gap will remain for some significant time. Here, interim solutions for adequate capability solutions will be needed.

- Instable portfolios, with growth strategies in potentially highly contested markets or in instable situations will require great capabilities from Next Generation leaders. If they can be assured quickly, the additional risk might be rewarded. If not, the portfolio to be inherited may set the Next Generation up for failure or place a life-influencing burden on them. Here, Senior Generation leaders might want to remember that the ultimate fulfillment of a life-long entrepreneurial journey is not the extent to which one builds a (unstable) portfolio, but the level at which a stable portfolio can be handed over to a well prepared Next Gen. That’s the ultimate entrepreneurial achievement!

In summary, strategies to reduce identified “Portfolio-Capability mismatches” can be focused on either increasing the capability supply of the family, or reducing the capability demand of the portfolio, or a combination of both. Options to increase the family’s capabilities can be the hiring of additional experienced non-family executives, the set-up of an experienced Advisory Board or to install a well-run Family Office with highly capable experts.

Options for reducing the capability demand of the portfolio can be the timely turn-around of company assets (with external resources) before the start of the leadership transfer, or the sale of portfolio parts and individual assets that do not match the given and foreseeable capability levels of the business family’s system, hence de-risking the overall portfolio allocation.

Using the “Capability Formula” and the “Portfolio zones” can trigger a constructive discussion about the future involvement of family members and portfolio strategies. In order to proactively design a swift transfer of the wealth embedded in the various assets, “facing reality”, as in identifying a match/ mismatch between the family’s capability and the portfolio is strongly recommendable. By doing so, Family Capabilities and portfolio strategies can be integrated, and the transfer of wealth becomes an opportunity for proactive Next Generation entrepreneurship, based on a realistic judgement, and subsequent preparation and education.

Sources:

- Davis, J., and Tagiuri, R. (1989): “The Influence of Life-Stage on Father-Son Relationships in Family Companies.” Family Business Review, vol. II, 1., pp. 47-74.

- Kepner, E. (1991): The Family and the Firm: A Coevolutionary Perspective. Family Business Review, vol. 4, 4: pp. 445-461.

- King, S. (2003): Organizational Performance and Conceptual Capability: The Relationship Between Organizational Performance and Successors’ Capability in a Family-Owned Firm. Family Business Review, vol. XVI, no. 3, September 2003, pp. 173-182.

Other readings on the topic:

- Accenture (2015): “The “Greater” Wealth Transfer Capitalizing on the Intergenerational Shift in Wealth”, Wealth and Asset Management Services l Point of View, 2015. From: https://www.accenture.com/us-en/~/media/Accenture/Conversion-Assets/DotCom/Documents/Global/PDF/Industries_5/Accenture-CM-AWAMS-Wealth-Transfer-Final-June2012-Web-Version.pdf, accessed 16. December 2016

- Barnes, L., and Hershon, S. (1976): “Transferring Power in the Family Business.” Harvard Business Review, July-August 1976, pp. 105–114.

- Barry, B. (1975): “The Development of Organization Structure in the Family Firm.” Journal of General Management, Autumn 1975, pp. 42–60.

- Beveridge, W. E. (1980): “Retirement and Life Significance: A Study of the Adjustment to Retirement of a Sample of Men at Management Level.” Human Relations, 33 (1), p. 69.

- Buhler, C. (1955): “The Curve of Life as Studied in Biographies.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 19, pp. 405–409.

- Butrick, F. M. (1978): “When Father and Son Collide.” The Packer, December 30, p. 9A.

- Cabrera-Suárez, K., De Saá-Pérez, P., García-Almeida, D. (2001): “The Succession Process from a Resource- and Knowledge-Based View of the Family Firm.” Family Business Review, vol. 14, 1: pp. 37-46.

- Danco, L. (1977): “Beyond Survival: A Business Owner’s Guide for Success.” Cleveland, Ohio: University Press.

- Frishkoff, P. A. (1994). Succession need not tear a family apart. Best’s Review, 95(8), pp. 70-73.

- Goel, S., and Jones III., R. J. (2016): Entrepreneurial Exploration and Exploitation in Family Business: A Systematic Review and Future Directions. Family Business Review 2016, Vol. 29(1), pp. 94–120.

- Gould, R. (1972): “The Phases of Adult Life: A Study in Developmental Psychology.” American Journal of Psychiatry, 129 (5), pp. 521–531.

- Gould, R. (1978): “Transformations: Growth and Change in Adult Life.” New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Handler, W. C. (1990). Succession in family firms: A mutual role adjustment between entrepreneur and next-generation family members. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 15(1), pp. 37-51.

- Handler, W. C. (1992). The succession experience of the next generation. Family Business Review, 5(3), pp. 293-307.

- Harris, D., Martinez, J. I., Ward, J. L. (1994): Is Strategy Different for the Family-Owned Business? Family Business Review, vol. VII, no. 2, Summer 1994, pp. 159-174.

- Hatum, A., and Pettigrew, A. (2004): Adaptation Under Environmental Turmoil: Organizational Flexibility in Family-Owned Firms” Family Business Review, vol. XVII, no. 3, September 2004, pp.237-258.

- Javidan, M. Performance Orientation; in: House, R.; Javidan, M.; Hanges, P; Dorfman, P.¸Gupta, V. (2004): Culture, Leadership, and Organizations. The GLOBE Study of 62 societies; Sage Publications, Inc.

- Levinson, D. J. (1978): The Seasons of a Man’s Life. New York: Knopf.

- Littunen, H (2003): Management Capabilities and Environmental Characteristics in the Critical Operational Phase of Entrepreneurship—A Comparison of Finnish Family and Nonfamily Firms. Family Business Review, vol. XVI, no. 3, September 2003, pp. 183-197.

- Mazzola, P., Marchisio, G., Astrachan, J. (2016): Strategic Planning in Family Business: A Powerful Developmental Tool for the Next Generation. Family Business Review, vol. 21, 3: pp. 239-258.

- Miller, D./ Le Breton/Miller, I. (2006): Family Governance and Firm Performance: Agency, Stewardship, and Capabilities. Family Business Review, vol. 19, 1: pp. 73-87.

- Niemelä, T. (2004): Interfirm Cooperation Capability in the Context of Networking Family Firms: The Role of Power. Family Business Review, vol. 17, 4: pp. 319-330.

- Schein, E. (1978): Career Dynamics: Matching Individual and Organizational Needs. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

- Sonnenfeld, J. (1988): The Hero’s Farewell: What Happens When CEOs Retire. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Chong K. P. (2016): China’s second generation shuns family business. Straits Times, December 18, 2016. http://www.straitstimes.com/world/chinas-second-generation-shuns-family-business, accessed 19.12.2016.

- Tokarczyk, J., Hansen, E., Green, M., Down, J. (2007): A Resource-Based View and Market Orientation Theory Examination of the Role of “Familiness” in Family Business Success. Family Business Review, vol. XX, no. 1, March 2007, pp. 17-31.

- Vaillant, G. E. (1977): Adaptation of Life. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Vaillant, G. E. and MacArthur, C. C. (1972): “Natural History of Male Psychologic Health, I: The Adult Life Cycle from 18–50.”Seminars in Psychiatry, 4 (4), pp. 417–429.