The rapid economic and social development of recent decades raises more and more questions about biodiversity and the protection of ecosystems. The spread of cultural landscapes is changing the habitats of many living beings. Banks, as frequent financiers of this development, must ask themselves to what extent they include natural criteria in their credit decisions.

Darwinism and biodiversity

Darwinism is very clear on one thing: evolution means that living beings that are better able to adapt to their environment are more likely to survive and reproduce (“survival of the fittest”). So, if the natural environment changes, be it in biodiversity (species diversity) or in ecosystems (habitats), then according to this doctrine, the “stronger” will win and prevail over less well-adapted creatures. But the thing is that changes that used to take centuries are now caused by humans in much shorter periods of time, and fewer and fewer living beings are finding enough time to adapt to the new circumstances. This leads to increased species extinction and a constant deterioration of living conditions for many organisms. Man is no exception in this regard. He, too, is only a living being that is exposed to the changes it has caused itself and, in extremo, destroys its own livelihoods. All living beings then have to live with the consequences.

There is no question about the importance of a healthy environment and the diversity of life for humans. Just as it is clear that people have an ethical responsibility for themselves and their actions. The exploitation of nature, which often goes hand in hand with economic and cultural developments, falls eventually back on humans and destroys many of the achievements of progress that are understood as certain. Humans must accept that they are both significantly dependent on nature and the services it provides, and that they also have a significant influence on changes in nature through their behaviour. This two-sided view is referred to as “double materiality” in the sustainability discussion and regulation.

The responsibility of people and companies for nature

The responsibility that applies to people can also be transferred one-to-one to the economy and companies, including banks. An economy can only function as long as companies obtain the necessary resources from nature, and essential ecosystem services can fulfil their function. However, the availability of “resources” such as clean water or valuable mineral resources is often taken for granted, just as it is expected that bees, for example, do not pretend to be tired during pollination, just as it is the case for bees and pollination services. We must be on our guard that the livelihoods that are assumed to be safe are not endangered by excessive use or exploitation.

Environmental and nature conservation are not an invention of our time. For generations before us, the protection of livelihoods was essential but were managed without the hype of our time. However, it must be acknowledged that expanding cultural landscapes requires new ways of protection, which makes the increasingly intensive discussion about biodiversity in relation to species diversity and ecosystems urgently necessary. Society assigns an important role to banks here. After all, they are in a position to intervene in sustainable economic and social development through their credit and investment policies. In addition, the measures on biodiversity and ecosystems require high financial resources, which are difficult to raise from the public sector.

Challenges for biodiversity and ecosystems

Nolens volens, banks accept the role intended for them and are now faced with the challenge of having to integrate biodiversity and ecosystem criteria into their credit decisions. This is in addition to the classic credit default criteria. However, this is not an easy task. In the field of climate change, scientists were at least able to agree on key metrices on greenhouse gas emissions and intensity, which facilitated external communication. This is not the case in the environmental sector. Professor Dr. Anna-Lena Kotzur, who has been studying the effects of biodiversity on financial institutions for a long time, notes “that such a generally accepted representative indicator for biodiversity does not exist and is unlikely to exist in the near future. Rather, a large number of key metrices must be taken into account that relate to the four foundations of life: life on land, life in the air, life in fresh waters, and life in the oceans.” She sees the reasons for this in the peculiarities of the individual habitats which are fundamentally different from each other. The diversity of biotopes ranges from coastal areas to deserts, from wetlands to alpine terrain. The fact that the challenges of biodiversity and ecosystems are often local phenomena (e.g. dried out peatlands, lack of bees) also contributes to this diversity, whereas climate change can only be solved globally.

The LEAP process in the corporate environment

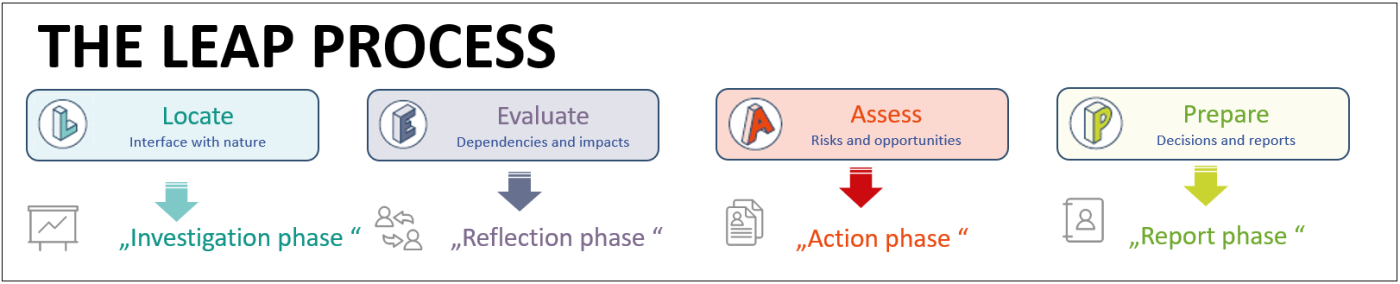

What applies on a large scale also applies on a small scale in the lending process. The business models and project plans of corporate customers who approach the bank with a loan request must be examined with regard to their dependence on nature and their impact on nature. So how can this be done in a structured way? Where does the required information come from? To this end, the very influential Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) is proposing the so-called LEAP process[1]. LEAP stands for the four process steps Locate, Evaluate, Assess and Prepare. Before starting the process in a company, it is recommended to precisely define the scope of the analysis due to the complexity of the task.

At the beginning, the process is based on an inventory of a company’s assets (“locate”). The points of contact (the “interfaces”) of a company with nature or the project to be financed are examined. These can be, for example, land areas near protected areas. This step is similar to a classic “inventory exercise”, only this time related to nature. Science-based tools such as ENCORE (Exploring Natural Capital Opportunities, Risks and Exposure)[2] can help.

The second phase involves determining whether a company is affected by biodiversity and ecosystems. Based on the results of step one, the dependencies of a company on nature and the effects of the company on nature are examined in accordance with the concept of double materiality.

The consequences of the analysis will be considered in phase three. Of course, the loss of biodiversity as well as the deterioration of ecosystems pose risks for a company that must be actively addressed. However, the transformation also offers opportunities that need to be seized in good time.

The fourth phase then summarizes the reactions, the “answers” of a company to the challenges. This can be done in the form of reports, presentations, but also in concrete measures with goals and metrics.

The LEAP process in the banks’ credit process

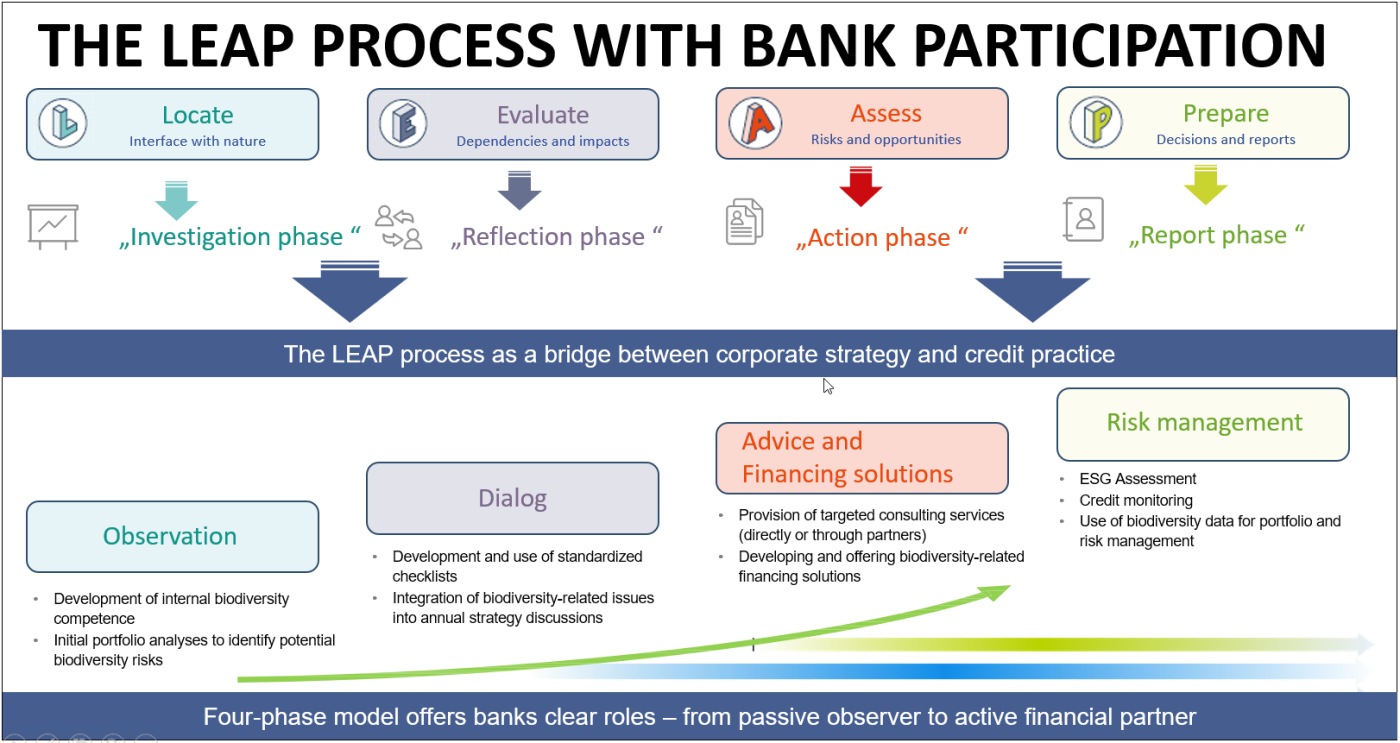

The LEAP process can be a very useful and helpful procedural model for business practice to systematically identify and manage biodiversity and ecosystem risks. But while many companies focus on their internal transformation processes, one crucial lever – namely the role of banks – is often underestimated. Banks have long been more than financiers, they can be important driving forces and strategic partners in biodiversity management. The prerequisite for this is that the role of the banks is anchored in the LEAP process in a targeted and phase-specific manner. Banks can be meaningfully integrated along the four phases – from passive observers to active financial partners.

Phase Locate – The Discovery Phase of the Company: In this phase, companies analyze their geographic locations and operations with an impact on nature. The initiative clearly lies with the company – banks are acting as observers for the time being. In this phase, however, banks can already lay an important foundation by building up their own expertise in the field of biodiversity in a targeted manner. They can continue to analyse sectoral biodiversity risks in their portfolio, identifying clients who are highly “dependent on nature” in order to proactively address them.

Evaluate phase – The company’s reflection phase: In the second phase, the company systematically analyzes the identified risks, dependencies and impacts from a materiality perspective. The company is still acting on its own responsibility – but the dialogue with the bank begins. Banks can provide initial impetus by systematically expanding the annual strategy dialogues with their customers to include biodiversity issues and supporting companies with standardised biodiversity checklists. It is important that the company is aware that the topic of biodiversity is increasingly becoming credit-relevant. In the context of taxonomy classification, the “do no significant harm” criterion is particularly relevant for biodiversity. Even a significant positive contribution to the achievement of an environmental goal must not have a negative impact on biodiversity.

Phase Assess – The company’s action phase: For the banks, a decisive phase is now beginning. As soon as the company develops measures to integrate the biodiversity goals into its business strategy, the bank is now in demand – as an active supporter and financing partner. In this phase, the LEAP process becomes a strategic bridge by translating corporate biodiversity goals into financing instruments. Banks are on hand as partners to offer solutions – for example in the context of earmarked ESG loans, structured KPI-linked loans or similar sustainable financing solutions.

Phase Prepare – The company’s reporting phase: The companies now report – internally and externally – on their progress, challenges and goal achievements. The bank evaluates the information – a key role in credit risk management – as it feeds directly into ESG assessment and credit decision-making, as well as ongoing risk monitoring. Furthermore, the bank can use this valuable information to analyse and manage its overall portfolio.

Summary

In summary, the LEAP process is a structured translation aid between nature and business – but its full potential only unfolds when the financial sector is also strategically involved. This creates a win-win situation. Those who take ESG seriously can no longer avoid the topic of nature – and banks that integrate biodiversity aspects into their lending business at an early stage position themselves as innovative and strategic partners to their customers. The LEAP process is therefore much more than just an analytical tool for companies – it provides banks with clear sales opportunities and real competitive advantages.

As shown, the LEAP process can provide a valuable introduction to biodiversity and ecosystem risk management. It supports both companies and financing banks in managing complex information requirements and creates transparency. Close cooperation between companies and banks is recommended, with the intensity increasing over the phases. While the banks initially only have an observing role, a highly active role is required from phase three at the latest, which is also about financing the opportunities and risks. After successful financing, the results of phase four then determine the credit monitoring throughout the entire financing term. Early cooperation between companies and banks is advisable in order to create mutual trust and to be on the spot quickly and in good time if financing is required.

[1] UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) (2023

[2] TNFD (2025), Guidance on the identification and assessment of nature-related issues: the LEAP approach